Image Copyright: The Stanley Picker Trust

Visiting the iconic interiors of Surrey’s Stanley Picker House and The Homewood

Design trends come and go, but I’m starting to wonder if mid-century modern is forever.

The minimalist movement first swept through US suburbs in the 1940s and Fifties, held on until the Seventies and regained popularity in the Noughties. It’s not dipped since and now dominates the retail market, from West Elm to FirstDibs and Sotheby’s.

As with many art and design movements, debate continues over what mid-century modern actually is. Experts broadly agree that it refers to architecture and furniture designed in the mid-20th century. Purists claim it’s specific to the post-war decade 1947-57. But as these secret gems of Surrey testify, the movement had already gained traction by the Thirties and flourished well into the Sixties. A classic had been born.

How can our homes benefit from its clean lines and understated elegance? How can a look rooted in a bygone era stay current? How can we take the best from this icon of period design and root it firmly in the present? I believe in taking inspiration from the masters themselves. So, when I was recently invited to visit two of Surrey’s best-kept interior design secrets – houses of the modernist period, I couldn’t refuse.

The first is the Stanley Picker house in Kingston-upon-Thames. Built for New York cosmetics mogul, Stanley Picker, it was his UK base, convenient for his make-up factory in Surbiton. Spacious and progressive, this rare surviving example of a late modern house remains largely unaltered since it was built and furnished in 1968. Designed by British Modernist architect Kenneth Wood it retains period furnishings, acquired through Conran Design Group and Conran Contracts, which connect perfectly with the interior layout.

Three standouts from my visit are influencing my current projects.

1) The house fits seamlessly into its landscape on a steep slope. This topography deterred most potential buyers but architect Kenneth Wood makes a feature of it, allowing the natural shape of the plot to inform and inspire his plans. Incorporating what we can’t change, without apology or disguise, can be the making of an original, successful design.

Exterior of the Stanley Picker House set into its landscape on a steep slope.

Image Copyright: The Stanley Picker Trust.

2) The architect and design team joined forces to create striking visual and spatial interest. A revolutionary double-height central hall with floor-to-ceiling windows forms an exceptional open-plan living area. Half-height curtains/blinds allow filtered light and privacy at floor level while the bare glass above floods the entire space with sunshine. This constant interplay between outdoors and in, layout and furnishings, light and space, is a model of integrated design.

View of the Picker House living area from the entrance hall gallery.

Image Copyright: The Stanley Picker Trust

3) Despite the open-plan layout and galleried levels, the interior is carefully zoned to create welcoming, cosy and intimate nooks within the overall living area. Modern interpretations of open-plan can create dead or gaping spaces: we can’t relax in a stadium environment. Impeccable zoning gives us the best of both worlds and the Stanley Picker interior is a masterclass in this.

The Stanley Picker House library with a view to the terrace.

Image Copyright: The Stanley Picker Trust

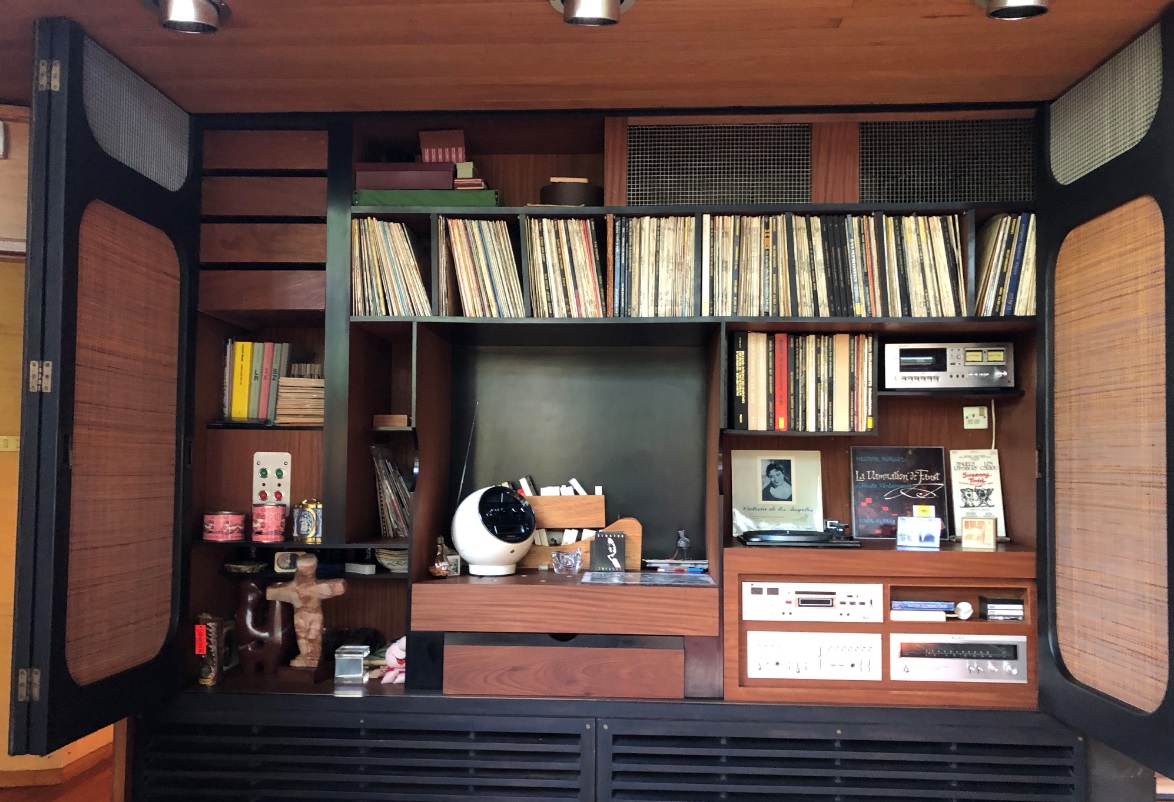

The media cabinet is a focal feature, paying tribute to Japanese simplicity with its textured screens and dark wood cubbyholes.

The media unit in the Picker House living area, designed by Kenneth Wood.

Image Copyright: The Stanley Picker Trust.

The second modernist house I visited is one of Esher’s best-kept interior design secrets: The Homewood, built just before World War Two by architect Patrick Gwynne for his parents. From the exterior, the house is a stark white box floating on slim pillars in landscaped gardens and is widely considered to be a Modernist masterpiece. Gwynne left it to the National Trust in 2003, stipulating that a family should live there and that it should be open to the public one day a week for six months of the year.

The Homewood, Esher, Surrey

While the outside is almost blindingly white, the interiors are alive with the rich and dramatic natural colours, textures and design classics of the modernist era. Gwynne loved maximising light. Many of the rooms are set at angles to profit from the way the light falls. His other design passion was storage, which he uses cleverly here to characterise and determine distinctive areas within the open-plan living spaces.

Photography of the interiors is not allowed, but the National Trust site has some enticing images, and, better still, details of how to visit the house.

Again, the show-stopper is the living area, drenched in light from three bays of horizontally-barred, Japanese-style windows which span the full 10 metre length of the space, creating a panoramic of the garden beyond. This Japanese influence extends inside with folding screens replacing walls, incorporating flow and flexibility for living into the core design.

It’s not everyone’s idea of domestic bliss – I’m not sure it’s mine. But certainly we can learn from its embrace of nature’s ochres and charcoals, leathers and woods; its bold accentuation of height and breadth. I came away having committed to memory the power of its striking furniture and features, vowing to let them inform my future designs.

The rear view of the house, The Homewood, Esher, Surrey.